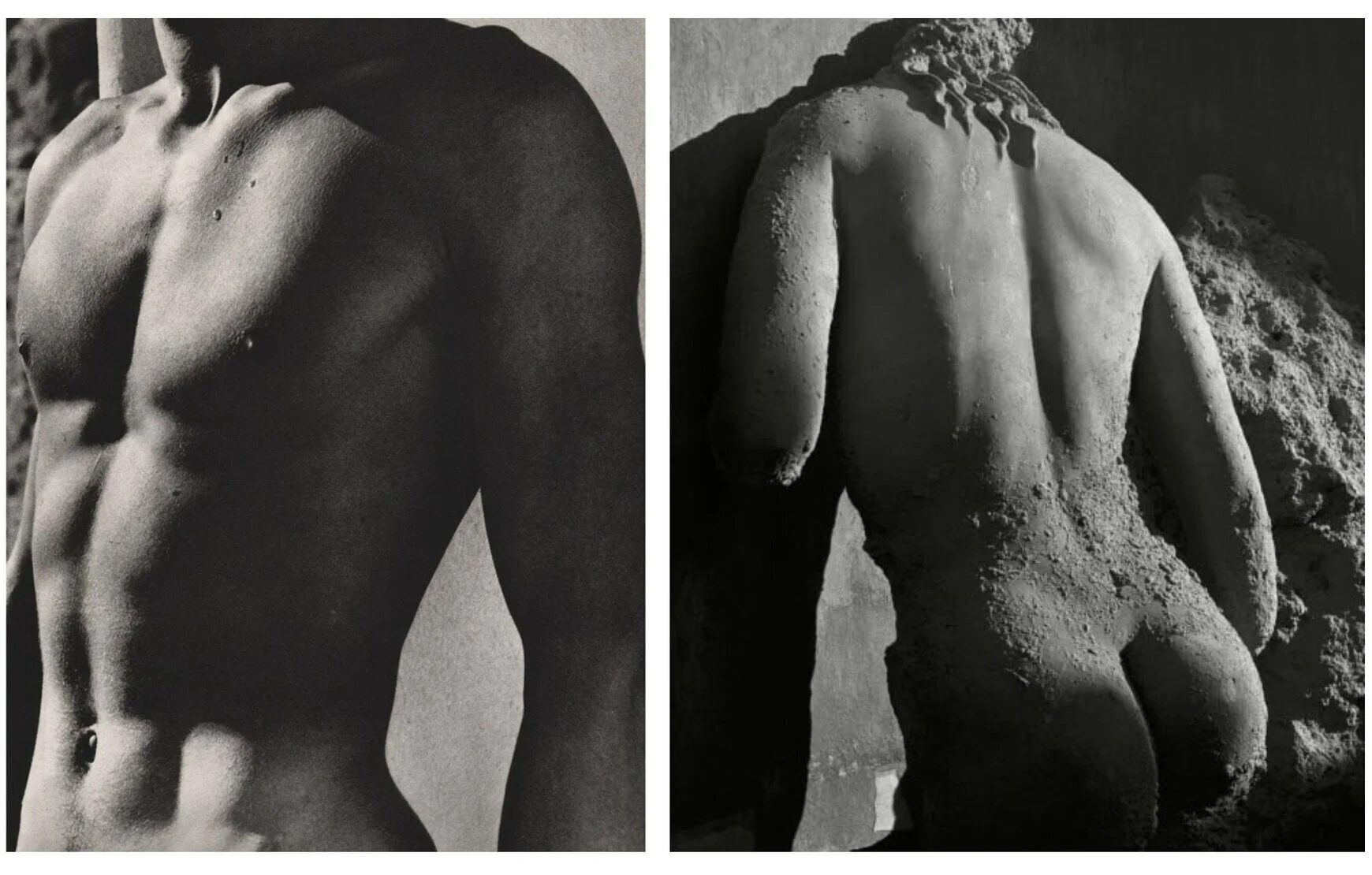

From June - July 2021, Magnum Photos in London presented Metamorphoses, an exhibition of works by the German photographer Herbert List (1903-1975). Along a single wall, photographs of chiselled male models and classical sculptures hung side-by-side, the line beautifully blurred between skin and stone. These images (taken in the Mediterranean in the 1930s) were curated in homage to the myth of Pygmalion, a Cypriote sculptor who falls so madly in love with a statue he has carved that it comes to life.

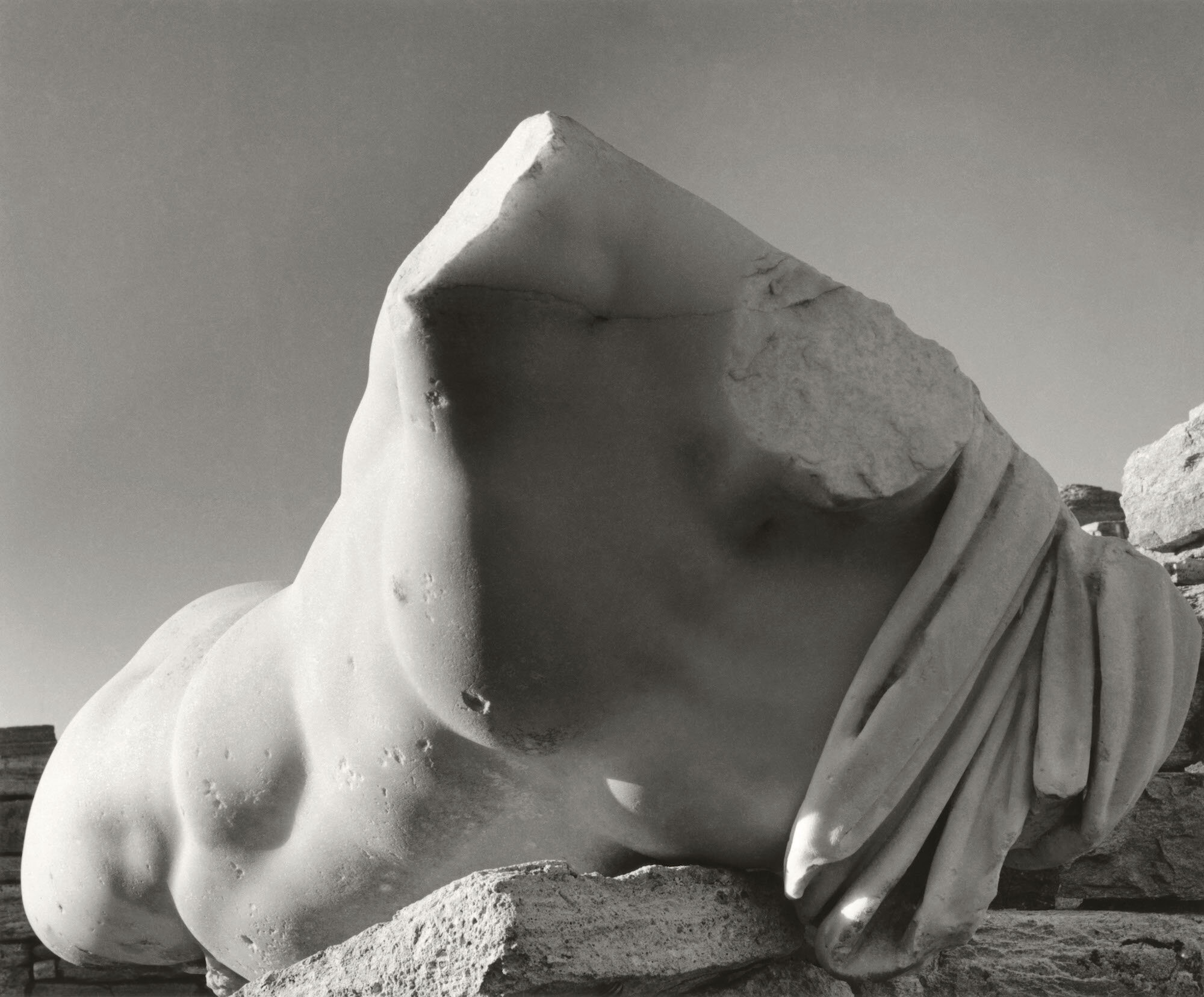

List’s knack for bringing out the life-like, sensual quality of sculptures is indisputable. By tightly cropping his images, focus is placed on particular parts of the sculpted anatomy. List’s composition, coupled with his shooting on high contrast black and white film makes each ripple and undulation of stone cast a jet black shadow which mimics the way light falls on real muscle and bone. You can’t look at the above statue (half-buried in rock and sand) without noticing the shadow at the centre of the statue’s back which tricks you into believing a spine and rib cage lie beneath. We momentarily see not lifeless earth hammered into shape, but something tantalisingly half-alive, as though the form were holding its breath.

List also breathes life into these sculptures by focussing on their imperfections. Despite statues having an eternal quality, stone outliving human flesh, List shows them caked in mud and their alabaster surfaces chipped and dented. In this sense, they resemble the scars and blemishes our own skin acquires with time.

Overall, Metamorphoses positions List firmly as a queer artist whose appreciation for the sculptures of antiquity allowed him to express his homoerotic desire and influenced the way he photographed his flesh and blood contemporaries. The juxtaposition of the two gives each human the same god-like gravitas as a statue. The above image, Wrestling Boys II, is cropped so the figures fill the entire width and height of the photograph, their proportions even more colossal than what in reality is the much larger sculpture, Theseus and Minotauros at the Tuileries. In turning a dense three-dimensional sculpture into a lightweight two-dimensional print, List condenses, as it were, time and space. What was once created over months or years involving hard manual labour can now be re-created afresh with simply the touch of a button. You could argue that taking photographs of statues takes the creative power away from the sculptor and transfers it to the photographer. The photographer re-fashions the sculpture, their choice of composition and framing investing it with personal meaning. In the case of Theseus and Minotauros at the Tuileries, List creates a triangle in the centre of the image which pulls focus across the broad shoulders of the lower statue towards the testicles hanging between the upper statue’s legs.

It’s difficult to look at List’s photographs without being reminded of the opening credits to 2017’s Call Me By Your Name, a film steeped in nostalgia for both the 1980s and the classical world. The statues in the credits symbolise a world in which male beauty was celebrated and where male-male desire (often expressed by older men towards younger boys) was a cultural norm. Hence the relationship that plays out between Elio and the classical art scholar Oliver (played by Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer in the film) has an air of naturalness and inevitability about it.

For List living in mid-twentieth-century Europe, expressing his own same-sex desire would have been far from easy. Photographing statues allowed him to hide in plain sight, his interest in the artworks of antiquity both innocent and a reminder that queerness is in fact timeless.

There is something achingly beautiful about the image below, which depicts the plaster masks of two male heads sleeping side by side with a heaven-like sky above them. It demonstrates how composing a photograph is tantamount to the creation of one’s utopian universe, as you have a certain level of control as to what to include within your frame, and what to leave out.

It was taken in 1937, a year after List (both gay and Jewish) left his native Germany. With this in mind, List’s photographs of perfectly formed, Adonis-like young men can take on a slightly sinister edge. Despite his being Jewish, you sense his aesthetic tastes may have been influenced by Nazi propaganda and the Nazi concept of their supposedly being a “master race”. Perhaps he felt able to draw attention to the physical prowess of his male subjects because of the Nazi’s obsession with physical fitness and athleticism. However, it’s worth noting List focused on the beauty of the human form irrespective of race or nationality.

List in fact belongs to a long tradition of northern European artists who have used the Mediterranean, its people and cultural heritage, as a way of expressing their own queer identities. This part of the world has long been synonymous with same-sex desire, despite the hostilities queer people have faced (and continue to face) in parts of southern Europe. List’s work shares similarities with the photographs of Wilhelm von Gloeden (1856 - 1931), although List’s models are thankfully older and treated more respectfully as individuals. In fact, List started taking photographs simply as a way of documenting his friends, who he eventually put in masks and arranged in tableaux. List’s models are not presented in overtly pornographic terms, as von Gloeden’s Sicilian boys often are.

By the time List died in 1975, his photographs were all but forgotten. Yet he was clearly ahead of his time, his work influencing photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts, as well as modern fashion advertising. Look at how Dolce and Gabbana’s 2017 Light Blue perfume advert (shot in Capri) echoes List’s photographs Flirt I. and Flirt at the Piccola Marina of 1935 (also photographed in Capri).

What stands out most about Herbert List’s work is its unapologetic focus on beauty and the very modern way his subjects are framed. If you look again at Dolce and Gabbana’s advertising campaigns from the 2000s, it’s clear the male form (albeit a hyper-masculine one) is on show for more than just the gaze of a heterosexual male. Kami Emirhan explains that following the gay liberation movement of the 1960s and the Stonewall riots, marketers, advertisers and brands capitalised on a new “gay market”. By the 1990s this market was extended to reach all men, and thus the “metrosexual” was born. In Mark Simpson’s 1994 essay Here Come The Mirror Men: Why The Future Is Metrosexual he writes, ‘metrosexual man contradicts the basic premise of heterosexuality - that only women are looked at and only women do the looking. Metrosexual man might prefer women, he might prefer men, but when all’s said and done nothing comes between him and his reflection.’

Nevertheless, When the male form is objectified in mass media, it is still often the source of ridicule or comedy. At the end of D&G’s Light Blue advert, just as David Gandy’s swimming trunks are about to be removed, the music cuts out and the director yells “Cut!”, in a way that suggests a male’s backside must not be seen, or the desires of the woman/non-heterosexual male can not be fulfilled. In Western societies, when the male form is objectified, there is an assumption it will somehow be perceived as “feminine” and by implication weak or less dominant, or that there is something narcissistic and dangerous about a male appreciating his own body.

The way List embraced his homosexual gaze so strongly and elevated his figures by comparing them to the works of antiquity makes his artistic vision extremely bold given the times he lived in. Looking at his work is like looking through a pair of sun-drenched binoculars that allow you to glimpse a halcyon world where the past glides over the present and meets the future.