The first Bill Brandt photograph I remember seeing demonstrates the breathtaking simplicity of his landscape photography: a thin white path runs diagonally across charcoal-coloured grass. It reminded me of Thomas Hardy's poem, “The Roman Road”:

The Roman Road runs straight and bare

As the pale parting-line in hair

Across the heath.

In fact, the writer, Lawrence Durrell, stated 'Brandt uses the camera as an extension of the eye, the eye of a poet'. The critic, Stuart Richmond, likewise describes Brandt as ‘a poet ethnographer with a strong sense of the surreal’. It's pleasing to see Brandt's photographs as akin to poems. Whether cityscape, landscape, portrait or a study of everyday life, the most consistent aspect of his photographs is the aura they give off. The atmosphere of a Bill Brandt photograph seems to seep, as it were, into your skin.

While it’s easy to equate black and white photography with the sombre and macabre, Brandt pushed these qualities to the extreme in the dark room, his use of high contrast light and dark creating a universe of mists and vapers beneath which hillsides lurch and cobbled streets ascend towards white, abyss-like skies.

Brandt’s aesthetic mirrors, in an almost clichéd way, the obscure elements of his biography. Born in Hamburg in 1904 to an English father and a German mother (both of Russian heritage), Brandt remained tight-lipped about his childhood, the First World War and the rise of Nazism making him ashamed of his German roots. What’s more, he disowned his German background, adopting the name ‘Bill’ rather than ‘Hermann Wilhelm’, claiming to have been born in south London rather than Hamburg. Looking at Brandt's output, you sense he was drawn to illuminating the darkness of the world, many of his photographs being shot at twilight or in the middle of the night, many London street scenes lit by moonlight rather than electricity.

It’s easy to see Brandt as a practitioner of photographic modernism, his style paralleling German Expressionist Cinema (classics like Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari come to mind) as well as the cinematography of 1930s and 40s film noir.

Brandt’s first major work, The English at Home (1936), is a classic example of twentieth century photojournalism which aims to capture English people and the English sensibility. On one level it holds a mirror up to English society, and has much in common with later works like Walker Evan’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) and Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958).

You sense Brandt desperately wanted to capture everything he saw as being quintessentially English. As a result, some photographs come across as though they have been taken with the eyes of a tourist. Past-times like fox-hunting, tea-drinking, punting in Cambridge, cricket, rowing, policemen guiding the London traffic and beef-eaters on watch outside Buckingham Palace take centre stage. Nevertheless, certain images illustrate his highly personal and more surreal way of seeing the world, which he was to embrace more fully later on in his career.

In this photograph the rocking horse resembles a creature from the children's book which has come to life and is listening attentively to its own story being told.

In ‘Sunday Evening’, three pairs of lovers embrace one another in a park. The camera is low to the ground, their bodies anonymous and statue-like, almost like the staggered stones of a neolithic ritual-site. The folds of their blazers and skirts speaks of a formality at odds with their intimate and care-free postures. The image carries a hedonistic and erotic charge, the lovers feeling like they belong more to a scene from the 1960s than the 1930s.

Elsewhere, well-to-do children at a birthday party stand frozen by the camera flash, the helium balloons around them like an other-worldly forest shrinking them to an even more diminuative size. The opulence and comfort of the middle class drawing room is almost at odds with the synthetic and modern looking balloons.

If there is a single theme running throughout The English at Home it is surely the extremity of class division in the decades preceding the Second World War, as well as the differences between the North and South of England. Even if the upper classes are not always directly photographed within their homes, their power is felt through their absence. ‘Parlourmaid prepares madam’s bath’ is photographed with a cold precision, the maid’s eyes shadowed and inaccessible beneath her large hair covering, her body arched low from the waste from habitually picking up of other people’s things. The tiles are shiny and the water crystalline, the gleaming whites contrasting starkly with the void of black worn by the maid. You can imagine the ‘madam' of Brandt’s title luxuriating in the hot bath, the viewer reminded that her pleasure is the result of another woman’s labour. Speaking to the BBC in 1983 about his photographs of parlourmaids, Brandt said "It is a different world. On the whole this wouldn't exist any more, and at the time it was quite normal”. Therein Brandt pithily outlines the role of a photojournalist: someone who photographs that which might be commonplace in the present conscious it will acquire significance in the future.

It’s worth bearing in mind Brandt’s photojournalism is the product of a man with a high social status. Although he is sympathetic towards his subjects from lower social classes, you sense genuine poverty was something foreign to him which the camera helped him experience as something of a tourist-voyuer.

Brandt also embraced the theatrical nature of photography, many of his images being staged. He drove these three children in his car to the top of their road so that he could photograph them beside this particular tree, buying them a bottle of lemonade to use as a sort of prop. The image feels far more illustrative and self-conscious compared to photographers like Helen Levitt or Tish Murtha who likewise documented children at play.

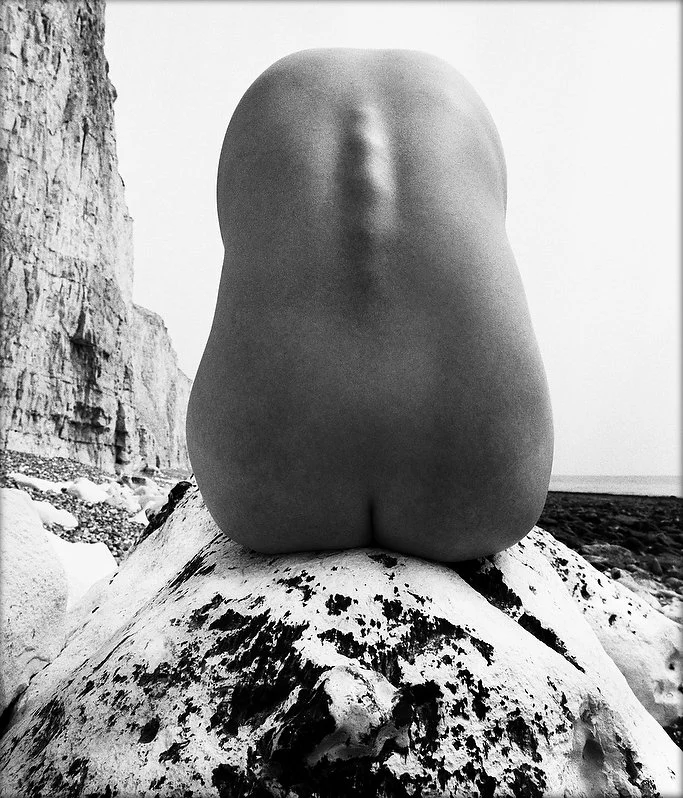

Brandt created documentary photographs with the eye of an artist, always favouring that which was constructed and aware of its role as a document or piece of art. He favoured medium format cameras as opposed to 35mm cameras, saying that pictures should be carefully planned and composed rather than being randomly "fired off”. However, the full force of his artistry seemed to emerge after he created nude portraits after 1945. These images have much in common with the work of artists like Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti. Moreover, Brandt’s development as a photographer was thanks to the surrealist artist and photographer, Man Ray, who he worked for in Paris in 1929. Man Ray said of photography: “It's not a question of reproducing reality, but of creating it.”

Brandt’s post 1945 artistry on one level occurred by accident. He asked the surrealist painter and photographer, Peter Rose Pulham, for a wide-angle lens because he wanted to photograph nude subjects in relation to the rooms they were in. Brandt didn’t realise the lens would create a distortion effect and make parts of the body on the edges of the frame longer than they actually were. The lens was created by Kodak in 1931 and initially used by the New York Police Department. It covered a 110° angle, allowing anything four feet or more from the camera to be in focus. Brandt’s nudes tend to be located in Victorian-style London bedrooms, and the mixture of old environments, classical forms and modern technology creates a distinct and at times unsettling aesthetic. Some look like they have been taken through a keyhole, the viewer placed in unexpected positions. Some look like poetic crime scenes, simultaneously erotic and icy-cold, the images appearing like some fantastical collaboration between Henry Moore and Jack the Ripper.

The camera's position below the women makes them more imposing, their bodies goddess or deity-like. The novelist, Chapman Mortimer, wrote in an introduction to ‘Perspective of Nudes’:

According to Brandt, modern cameras are designed to imitate human vision and perspective, and he says that having used them to photograph London in the thirties and during the war he began to find them too perfect. They reproduced life like a mirror, and their efficiency prevented him from entering the mirror…He wanted a camera…that would give him “an altered perspective and a less conventional image.” He hoped for a lens that might see more: that might see, “perhaps, like a mouse, a fish or a fly.”

Fish-eye lenses are now commonplace and have been popularised by contemporary fashion photographers like Tim Walker:

The zenith of Brandt’s artistic experimentation was reached when he took photographs on the beaches of Sussex and Northern France in the late 1950s. His extreme close-ups of fingers, ears, knees and arms transfigure the human form, forcing us to marvel at how different parts of the body have been engineered. When viewed in succession, they remind us how unique, varied and often alien different parts of the body can be, and that our joints and vertebrae also mirror certain natural forms found within a landscape. By moulding the human body onto backdrops of pebbles and sea, Brandt reminds us that the human body is a landscape in and of itself, a topography both of the earth and uniquely itself and separate to its surroundings.

Lastly, Brandt’s beach images remind me of the poem “To His Mistress Going To Bed” by the Metaphysical poet John Dunne, who envisions his lovers body as being like a whole continent/land mass:

O my America! my new-found-land,

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man mann’d,

My Mine of precious stones, My Empirie,

How blest am I in this discovering thee!

To enter in these bonds, is to be free;

Then where my hand is set, my seal shall be.