In her living autobiography, Real Estate, Deborah Levy describes seeing a woman in New York feeding pigeons on the sidewalk: ‘I wondered if throwing seeds to the pigeons was her way of feeling valued and loved.’ This moment, although brief, made me think of Vivian Maier, someone who by the end of her life would talk to herself on park benches and give unwanted advice to strangers as they walked by. She had become like the archetypal ‘bird-lady’ living on the margins of society, yet in plain sight, making little attempt to mask her eccentricities.

Looking at Maier’s body of work, you sense she took photographs perhaps not to feel valued or loved, but as a way of expressing her innate power. On paper, her life speaks of hardship and a certain level of powerlessness. Born in New York in 1926, Maier had an unstable childhood spent travelling back and forth between The Bronx and the small French village of Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur. By 1930 her father had more or less abandoned the family, and by the age of 25 she was working in a sweatshop. In 1956 she became a live-in nanny, and for the next forty years, she worked for dozens of families in both Chicago and New York.

Working as a nanny was in many ways a stroke of genius, as it meant she could dedicate herself to street photography under the guise of going for long walks with prams and a bevvy of children. The children she looked after describe trying to keep up with her as she marched them through deprived and often dangerous parts of town, taking picture after picture at break-neck speed. Being a nanny also afforded Maier, as Virginia Woolf famously put it, a room of one’s own. Although this room was not in a house she owned, it gave her a space in which she could operate as an artist on her own terms. She filled her various bedrooms with cardboard boxes containing newspapers and thousands of undeveloped film canisters. She accumulated so many boxes that one employer had to add extra support to the room below to stop the ceiling from falling down. The key to this room was attached to a string around her neck, and she gave strict instructions that no family member was to ever try and enter her room at any time.

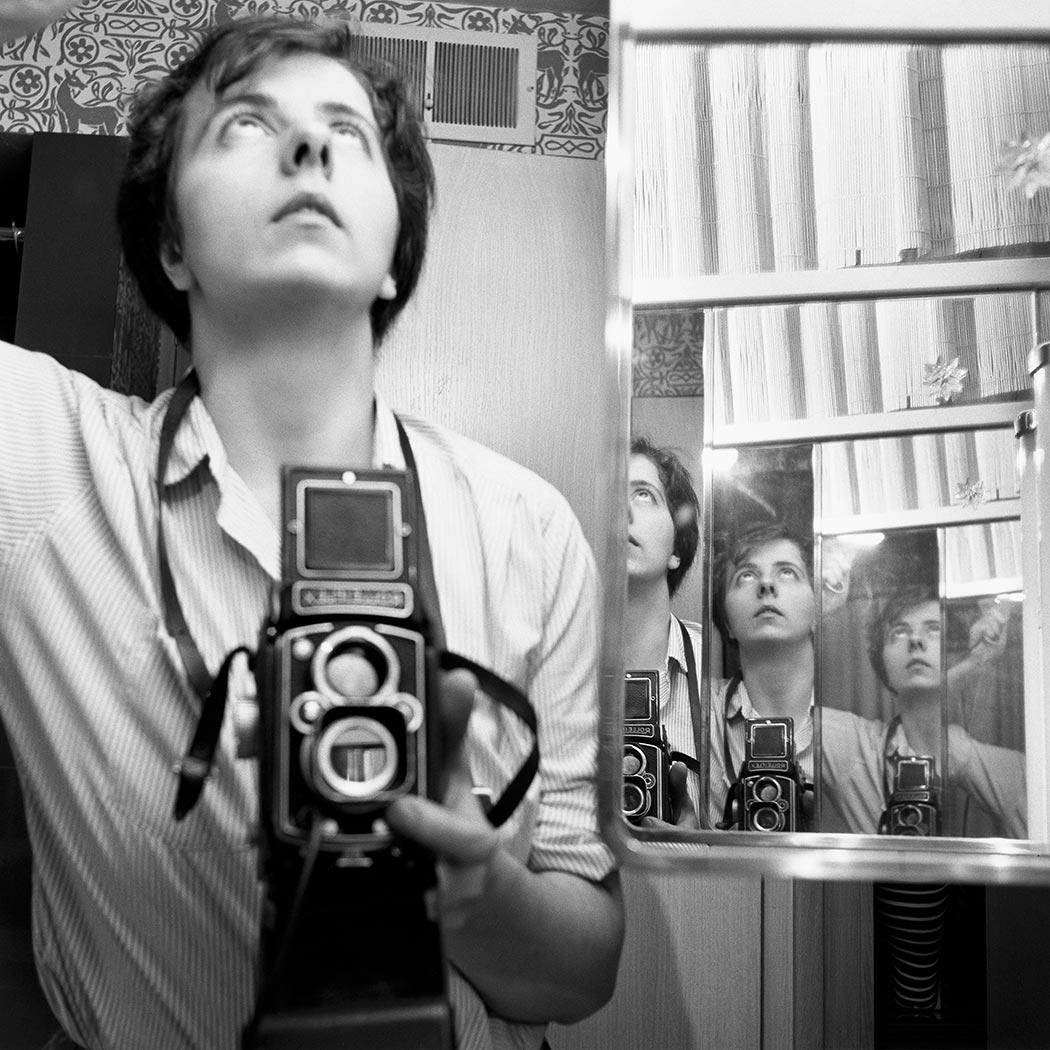

In Vivian by Christina Hesselholdt, a fictionalised account of Maier’s life, one of Vivian’s employers regrets having given Maier a room situated at the very top of the house. She worries it puts Vivian above her station, allowing her to preside over the family like a monarch, her employers and the child she is paid to help raise situated beneath her. Looking at Maier’s self-portraits, one feels the force of her character and intelligence. It looks as though she had the ability to see through people and the world around her with razor precision. She took many self-portraits in which she looks at her own reflection in mirrors. You sense in her eye a flicker of recognition, as though she knows the person she is looking at to be an artist. In these secretive portraits, she possesses a status above the one dealt her by fate.

It’s worth noting Maier took many photographs where her silhouette stretches along the ground, her body appearing larger than life and formidable, while also resembling the caricature of a detective or spy.

The below photograph shows, in the place where Maier’s heart would be, a Horseshoe crab. This prehistoric creature is in fact more closely related to spiders and scorpions than crabs. I wonder whether, in the moment of taking the photograph, she felt a kinship with this spiky, otherworldly and misunderstood creature.

Looking at Maier’s street photography, it becomes clear she was drawn to documenting people at the other end of the social spectrum to the families she worked for. Maybe the world of middle-class suburbia angered her, and she saught to document and elevate the world she had known as a child. African-Americans and people of colour appear frequently in her work. Perhaps she sympathised with their social marginalisation and used photography as a way of documenting their lives and reframing their identities. In the below photograph, a man rides a horse through the streets of New York, like a knight and his steed heroically surveying an urbanised, fairy-tale kingdom.

It can be difficult to know what compels us to take photographs of certain people and frame them the way we do. Although Maier’s photographic eye can sometimes feel dispassionate, as if nothing more than voyeuristic curiosity has compelled her to take the photograph, at other times you sense she is trying to get her own back on the world and its injustices.

In Hesselholdt’s Vivian, the writer obliquely suggests Maier may have suffered emotional/sexual abuse at the hands of her alcoholic father and brother Karl, who later suffered from schizophrenia and who died in a mental asylum. Although this abuse has never been corroborated, it might make sense of aspects of Maier’s life and work. She fragmented her own identity by frequently changing the spelling of her name, going by ‘Vivienne Maier’, ‘Mayer’, ‘Meyer’, ‘Meyers’ and even ‘Miss V. Smith’. Several people who she looked after as a nanny have said she could be prone to extreme mood swings and cruelty and that she would sometimes force-feed them.

I personally find the photographs she took of men sleeping in public significant. The men below (who may or may not have reminded her of her brother and father) would have held a status above Maier purely because of their gender. Armed with a camera, you sense she has the upper hand over them and is exposing the weakness of the male body at its most vulnerable. These men presumably felt safe and secure enough to sleep in public, meaning these photographs also document aspects of male privilege. Unlike Maier, who could only operate as an artist in the secrecy of her locked bedroom, these men do not differentiate between domestic and outdoor space. Rather, they have the privilege of living their lives out in the open.

Her photographs of wealthy New Yorkers also have a slightly mocking quality about them. While the women in the first two photographs are dressed elegantly, their expressions are far from cool and collected. They appear taken aback by Maier who (we can infer) showed little respect for their personal space or status. Through her lens, they are like frightened, exotic zoo animals caught behind glass.

Nevertheless, Maier’s photographs also offer glimpses of profound tenderness, beauty and humanity:

Hesselholdt even wonders whether taking photographs was Maier’s emotional response to her father walking out on the family:

Vivian did not begin in earnest…to take photographs until the late forties, when she stopped seeing her father/when he stopped seeing his children/when father and children stopped seeing each other. Was that why? Father is gone, in future, I (Viv that is) am going to preserve everything of significance that crosses my path.

Was photography a way of preserving moments that she desperately wanted, but was unable, to share with a loved one/parent? Was it her way of controlling the uncontrollable? Perhaps photography was something more than that for her, a way of proving her existence, a way of saying: “I am here, and this is the way I see the world, and this is what I want the world to see after I’m gone.”

Like the best kinds of people, Maier led multiple lives, and it would be a mistake to think of her simply as the eccentric nanny who lived in the attic. Remarkably, In the late 1950s, she acquired real estate of her own after one of her French relatives died and left her a small farm in Saint-Julien-en-Champsaur. Selling this farm allowed her to travel the world, and between 1959-1960 she took photographs in Los Angeles, Manila, Bangkok, Shanghai, Beijing, India, Syria, Egypt, France and Italy.

What defines Maier is the mystery surrounding her life and work. She kept her photographs hidden from public view, and it was more or less by chance that her negatives were found, developed and publically exhibited after her death in 2009. The fact that there are so many questions left unanswered as to why she never showed her work to anyone, how she felt about photography and about her own work, means she holds more power in death than she did in life. Her silence ensures that each image she took speaks for itself.