When I was around fourteen, a friend of mine lent me the photography-book, Diary of a Century, containing the early photographs of Jacques-Henri Lartigue (1894 – 1986). I was amazed to see black and white Edwardians for once not scowling at the camera in poses of awkward formality, but people who were leaping, skipping, tumbling, falling and flying through the air, all smiling as they did so. It was as if movement and the excitement it brings had been captured on film for the first time. Most astonishing of all was learning these images had been created by a child; Lartigue being only seven years old when he was given his first camera in 1901.

Perhaps only a child (belonging to a family of considerable wealth) could have created these images. You get the sense the adults in each photo are performing for Lartigue as part of a game or simply as a way of keeping him entertained. Hence each photo has an intimacy, immediacy and informality about it which might not be there had he been a fellow-adult.

One of my favourite photographs from this era, titled My Nanny Dudu, shows his nanny having just chucked a large, bouncy looking ball high into the air. Taken in 1904, it shows a woman who at the time must have had a lower social status than the ten-year-old boy photographing her. However, there is something pure and egalitarian about Lartigue’s photographic eye. With her dexterous arms outstretched, she looks powerful, as if feeling the force of her own physical strength. There is also something child-like about the way she looks up, momentarily mesmerized by the simple process of the ball being sent high into the air and then coming down again. Even with his child’s gaze, Lartigue the photographer is making sense of the world around him, and in this image he captures the wonder that is gravity. You could go as far as seeing My Nanny Dudu as the photographic equivalent of the famous apple falling on Isaac Newton’s head.

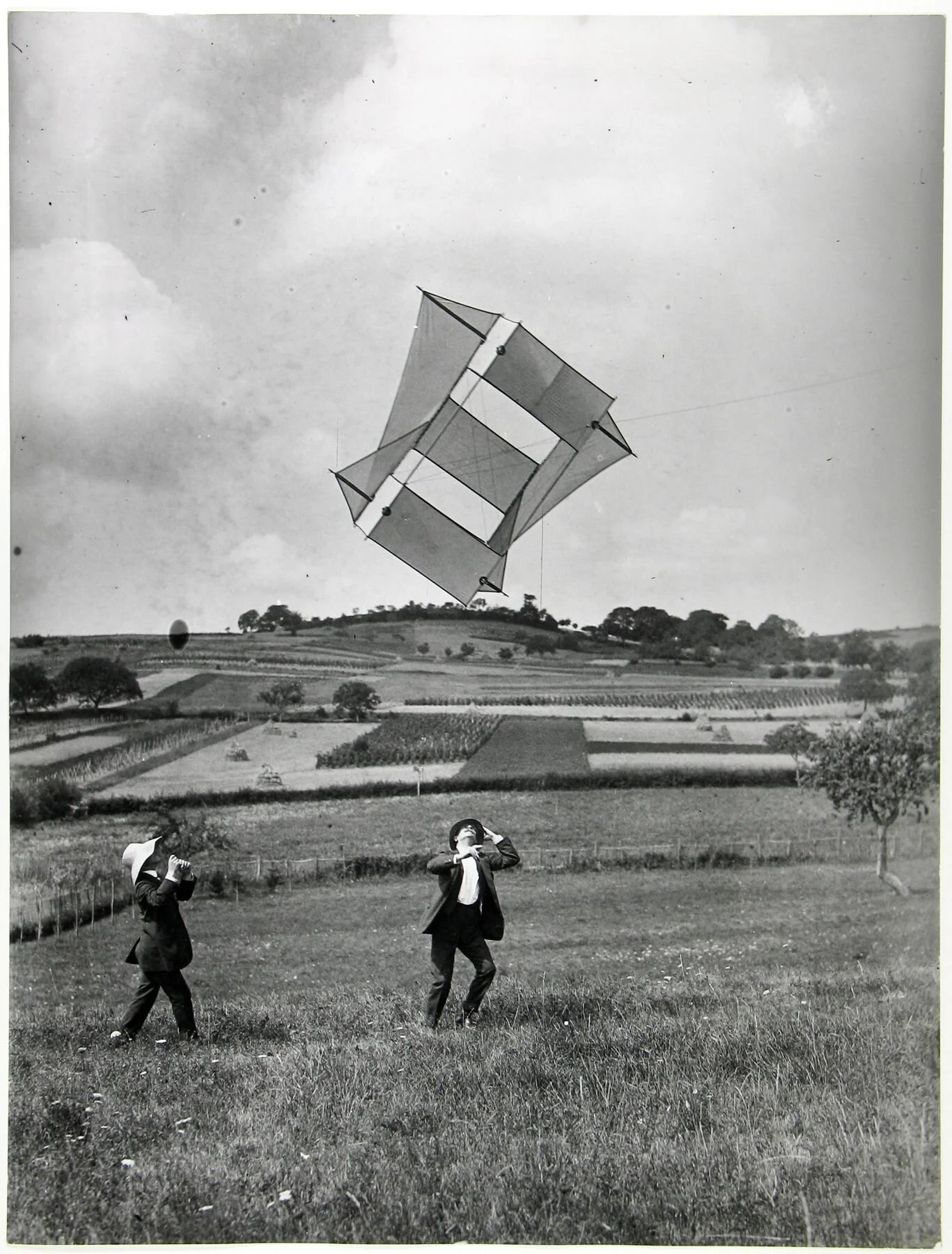

Many of Lartigue’s early photographs metaphorically keep Newton’s apple floating in the air. He recognized that if photographs suspend time, then the person or object photographed can likewise appear suspended or imbued with magical powers. Thanks to his camera, Lartigue made the make-believe of child’s play come true, his family and friends’ feet hovering in the air like the Darling children snapped en-route to join Peter Pan in Neverland.

Lartigue’s obsession with capturing people in the air is unsurprising given that interest in aviation was at its peak around this time. The Wright brothers successfully achieved lift-off in their pilot-controlled plane in 1903, while amateurs like Zissou, Lartigue’s older brother, were building and trying out their own DIY flying machines. Diary of a Century is a great title for a book chronicling the birth of aeroplanes and motorcars, inventions that would have such profound effects on the twentieth century (as well as the current century).

Lartigue’s images are also windows into the Belle Époque and a world lost forever. Like Proustian Madeleine cakes, they are highly evocative and filled with the energy and joy of a gilded childhood. Some are like impressionist paintings come to life, and as a child Lartigue was lucky enough to meet the Impressionist painter, Monet, remarking “It was like meeting Santa Clause, such was my excitement.” The nostalgia of these images is enhanced by the fact these care-free days of bourgeois fun and games were to come to an abrupt end with the onset of the First World War in Northern France.

These images were not seen by the world until 1963, when Lartigue was 69 years old. It was more or less by chance that, when travelling to New York with his third wife, Florette Ormea, he was introduced to John Szarkowski, the newly appointed director of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art. Lartigue showed his early photographs to Szarkowski who was so impressed that the following year, Szarkowski organized the first-ever exhibition of Lartigue’s work.

Susan Sontag wrote in 1977 “It is a nostalgic time right now, and photographs actively promote nostalgia…All photographs are ‘momento mori’. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

The fact Lartigue’s images are snap-shots where time is sliced out and frozen in such a precise and obvious way make them all the more nostalgic. Thinking back to My Nanny Dudu, for example, we know that the year 1904 will never exist again, but we also know that the bouncy ball in the picture will never be seen from that particular angle in the air again, and it will never be thrown by that particular woman in that particular way again. It’s therefore almost impossible to look at Lartigue’s images (even in the 1960s) without feeling nostalgia for the past and pathos at the fact nothing truly lasts forever.

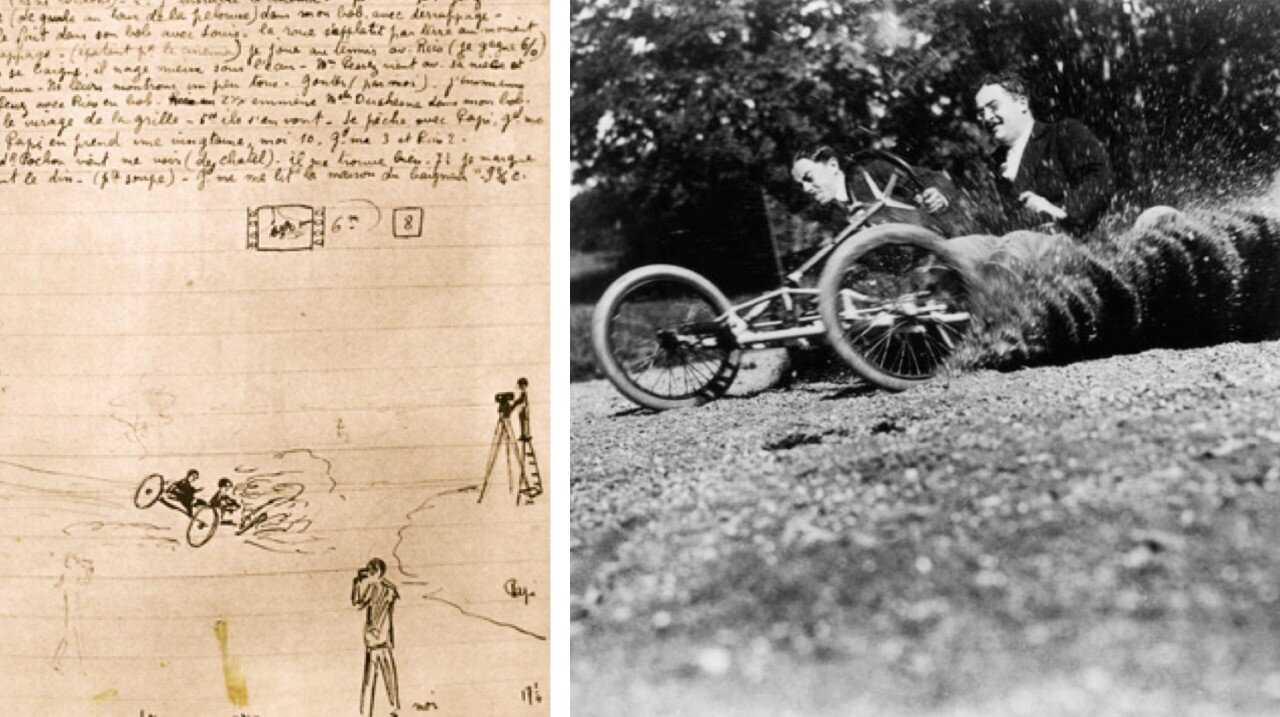

Yet I’d argue his photographs are not great simply because of their time-travelling qualities, but because of Lartigue’s mastery of composition and shooting in black and white. When not behind the camera, he worked as a painter, remarking “I have two pairs of eyes, one to paint and one to take photographs.” With this in mind, we can view him as an artist aware that he was simultaneously creating art through photography, which was itself a relatively new medium which blurred the lines between art and science. The journals he kept, even as a child, attest to the fact he was a draftsman of sorts, many containing drawings of the moments he had photographed that day. By keeping these diaries he could document how he thought an image would turn out versus how it actually did, as well as pinpointing what it was that interested him about particular subject matter, and what he wanted to capture next.

In 1983, Lartigue was interviewed by the BBC for their Master Photographers series. When asked “Is there a decisive moment for a photograph to be taken?” he responds “Definitely, but it’s the fraction of a second…It’s like a tennis match. You anticipate the moment. You do it before you’ve had time to think.”

In the same documentary, when asked whether he enjoys taking photographs in colour, he replies “Yes and No. They don’t last. They change colour”, a statement which feels very much of its time considering there are now so many digital images which exist more on pixellated screens than they do printed in ink on paper.

In Lartigue’s exquisite colour photography, a limited colour palette is used, as if recreating the two tones of black and white:

Lartigue is often referred to as an amateur photographer, in so far as taking photographs was a life-long hobby for him that helped him document those closest to him as they pursued various leisure activities. Moreover, he was not the only one having fun with a camera in the early 1900s. As his biographer, Kevin Moore states,

"All the jumping and flying in Lartigue's photographs, it looks like the whole world at the turn of the century is on springs or something. There's a kind of spirit of liberation that's happening at the time and Lartigue matches that up with what stop-action photography can do at the time, so you get these really dynamic pictures.”

What sets Lartigue apart from other amateurs is that his eye was masterful, his air-born turn of the century figures framed in such a way which captures the atmosphere of childhood, as well as the world of the Belle Époque and those privileged enough to enjoy it. The word “amateur” comes from a French word simply meaning: “lover of”, and in this sense, Lartigue is surely the greatest of amateurs, his love for photography as an art form shining through in every picture he took.

What’s also significant is that he continued to shoot people jumping in the air well into his later years, regardless of the social upheavals and wide-scale suffering brought about by the two World Wars which dominated the twentieth century. I’d like to think his air-born figures perhaps speak of something more profound, of Lartigue’s love of life, of the indomitable human spirit, and our ability to release our inner-child, to play, to dream, and defiantly jump for joy no matter what life brings our way.