The British artist and photographer, Ingrid Pollard (b.1953, Guyana) is probably best known for her works which focus on people of colour and their relationship with the English Countryside.

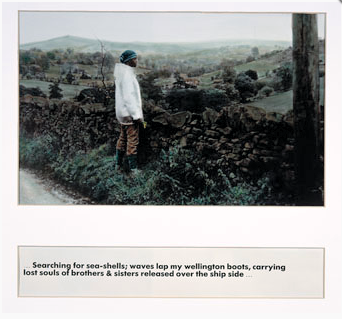

In Pastoral Interlude (1988), Black people are photographed in the Lake District, a space commonly associated with white people. Individuals are positioned beside walls, fences and rivers, topographical features indicative of borders, boundaries and liminal spaces that occur often in Pollard’s work. Paired with each image are words that powerfully evoke how it feels to be othered in Britain, a country whose “Greatness” and wealth was largely dependent on the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

In 1992, Pollard created a tourist postcard called Wordsworth’s Heritage, which depicts herself and other Black people in the Lake District, their faces contrasting with the caucasian, chocolate-boxy profile of William Wordsworth in the centre. These postcards appeared on 25 billboards in urban areas. As a piece of public art, the work makes you think of many things: tourism, leisure, freedom of movement, land ownership, class, nationhood, the labour involved in putting up billboards themselves, as well as the distances travelled by postcards and what they represent.

More than anything, Wordsworth’s Heritage seems to ask the question, If someone lives in a country, why should certain parts of that country feel inaccessible to them? In this sense, it feels just as important today given the struggle for racial equality continues into the 2020s. A recent report estimated only 1% of visitors to UK national parks come from BAME backgrounds, sighting language, awareness, safety, culture, confidence and perception of middle-class stigma as reasons. Having said this, there are plenty of individuals like Zahrah Mahmood (aka The Hillwalking Hijabi) and groups like Black Girls Hike who challenge these statistics. The Instagram page, Bumpkin Files, also sets out to document Black life as it has been lived in Britain beyond London.

Pollard’s work reminds me (even if it’s stylistically very different) of the American photographer, Tyler Mitchell’s photographs. In I Can Make You Feel Good and Dreaming In Real Time, Mitchell is concerned with representing Black people engaged in leisure activities. Mitchell states:

…Obviously, we do enjoy leisure time, that’s a global thing. But my work is about bringing forward these ideas of leisure and play as radical things, because we’ve societally, politically, and within ourselves—in our psyche—been prevented from enjoying those freedoms.

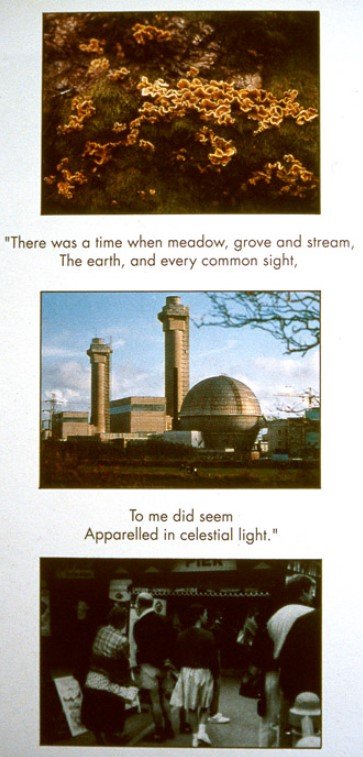

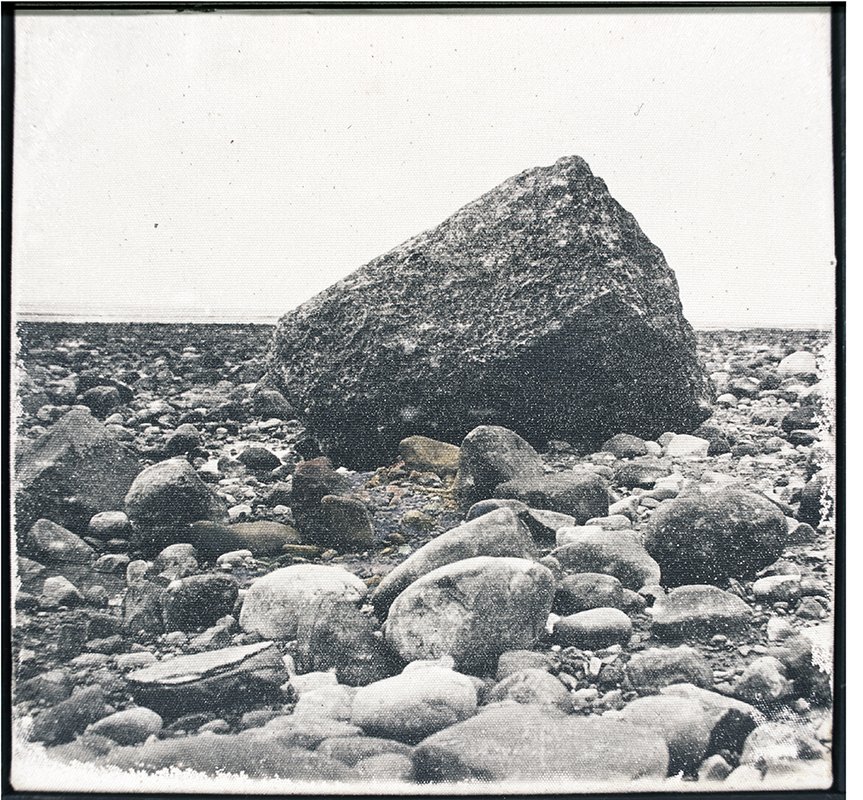

What might get overlooked when it comes to Ingrid Pollard is the breadth of issues she has explored throughout her career and the variety of mediums that have given them life. Pollard’s earliest work, The Cost of the English Landscape, is not just about Black bodies moving through white spaces but about the tension of idyllic and “natural” landscapes co-existing with the threatening, unnatural and violent quality of nuclear power. Through this work, we see nuclear power as both ominous and an ironic manifestation of the sublime, super-human and awe-inspiring qualities that inspired the English Romantics.

In Contenders, Pollard explores masculinity; how it is performed, how it shapes the human body, and how a certain type of male physique is made desirable by advertising and the media. This series wouldn’t have been at all out of place in The Barbican’s 2020 Masculinities exhibition.

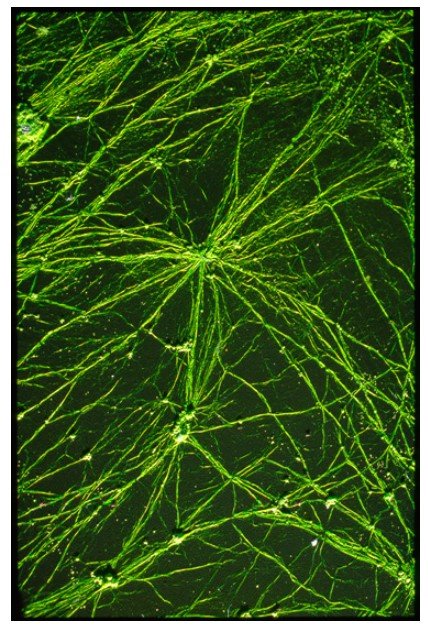

In 2001, Pollard exhibited one of her most interesting works, vast three-metre by three-metre prints in a group exhibition organised by Autograph called Landscape Trauma in the Age of Scopophilia at The Gallery, Southwark Park. Each work looks like marble or some type of metamorphic rock, as though Pollard has zoomed in with a microscope on part of a geological survey of Great Britain. In actual fact, Pollard artificially constructed the images with the intention of portraying the turmoil of the rural British landscape and the way it has been injured by politics, as well as cultural and natural forces.

One image in particular is as visually arresting as it is rich in possible meanings. Pollard speaks of the rural landscape being injured, and it’s worth noting that 2001 saw the foot-and-mouth outbreak devastate the countryside, culminating in the slaughter and burning of over six million farm animals. The work could be seen as an organ, its physical quality recalling the tradition of body politic imagery. The dominant colours, white, blue and a murky blood red, also recall the colours of the union jack, and in this sense, the work is a metaphor for both Britain’s physical and psychic history. It appears both literal and physical (like rock) as well as being highly abstract. To my eyes, the arrangement of colours is similar to the English Romantic painter, JMW Turner’s painting ‘The Slave Ship’ which represents the moment 132 African slaves were thrown overboard because there was insufficient water for all to survive the voyage.

Given Pollard’s interest in the 17th and 18th centuries, as well as William Wordsworth and what landscapes meant to Romantic writers, it’s worth noting the marbled effect in Landscape Trauma resembles the marbled book covers popular across Britain and Europe at this time. European paper marbling was an imitation of ancient Asian and Islamic Middle Eastern texts. Hence the marble effect contains within it the swirling inter-cultural historical soup that defines British culture itself.

Perhaps in this painting-like photograph, Pollard is commenting on the idea of ‘England’s Green and Pleasant Land’ (as popularised by William Blake in Jerusalem):

Hettie Judah discussed the politics of landscape imagery with Pollard for Frieze in 2019 and its relationship to colonialism. Judah considered how we are encouraged to either look up at or down upon a landscape, often by including a single figure surveying the landscape who stands in for the viewer. Pollard replied

It’s not just looking at it. It is very much about claiming it! Then there are people digging in the background: what’s their view, looking at the soil and the seeds?”

In Landscape Trauma, the distorted crevices, fissures and sludgy swirls ingeniously create the impression we are looking down at the earth from a great height, as well as looking up at it, as though our eyes are minerals lodged within the earth’s crust. One could relate this ambiguous placement of the viewer to Pollard’s Caribbean heritage and the liminal sensation of being connected to two places at once. However, it feels more like we are placed in a non-human realm and are being encouraged to experience the chaotic cosmic forces that shape the universe itself. Either way, Landscape Trauma disrupts what is associated with landscape art. Instead of creating the impression of peace and harmony, the landscape is made volatile and violent, but also sublime in its abstraction.

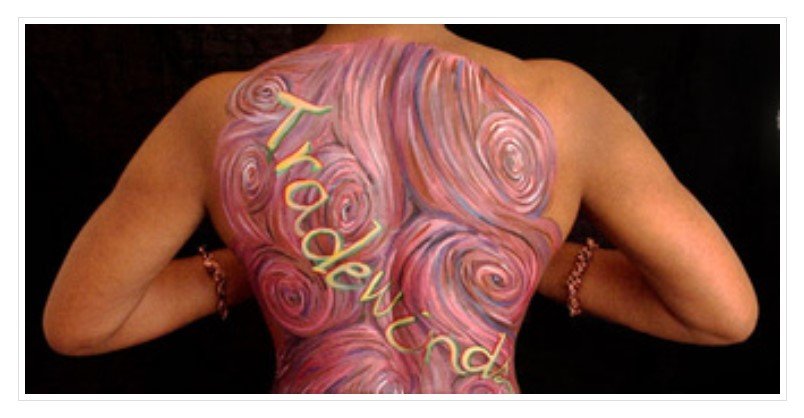

It’s safe to say Pollard is interested in the elemental forces that shape the world. In Trade Winds, for example, she explores the root causes that made the slave trade possible.

Pollard reflected upon how the Sun heating the air at the Equator and blowing from east to west enabled European merchant ships to travel from Africa to the Caribbean. These ships’ return to Europe was made easier by the Gulf Stream blowing from west to east. In this sense, historical events are made sense of by considering their geographical and meteorological context, the fate of whole civilisations being shaped by something as fundamental and uncontrollable as planetary air currents. Pollard states:

The fragility of the ceramic paper boats echoes the perilous journeys of all those beings carried through the Gulf Stream.

In 2013, Pollard had a residency at Highgreen in Northumberland in which she created a portable camera obscure used in collaboration with the local community. The outcome of the residency was Regarding the Frame, which includes a set of images that simply but no less powerfully document the changing seasons.

I would argue the most distinguishing feature of Pollard's work is its materiality. You can't look at her photographs without appreciating the process of developing a photograph: the toning, hand-tinting, enlarging and printing which makes each image unique and the work of a skilled artisan. Thinking again of Landscape Trauma, we are reminded that photographs do not just appear by magic, but instead come from the earth. The word ‘trauma’ could even suggest the earth is being anthropomorphized, with elements being extracted against their will, as it were, in order to serve the purposes of the photographer/artist. After all, creating a photographic print involves natural resources like carbon, ink, silver, aniline, resin and gelatin.

As Pollard herself states:

My practice is about photography and its history, method and material qualities. It can take the form of landscape or something else, but it is always about photography. It’s an obvious thing to say, but it doesn’t get said often.

Ingrid Pollard: Carbon Slowly Turning is showing at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes from 12th March - 29th May 2022.